17-year-old Jefferson He unpacks the UK’s ambitious new plan for innovation and growth in AI

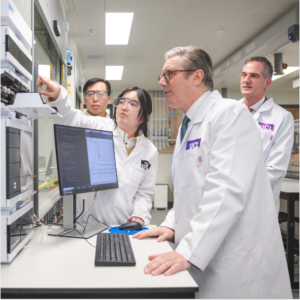

Prime minister Keir Starmer and technology secretary Peter Kyle visit University College London East for the AI plan

Picture by: Alecsandra Dragoi | DSIT | Flickr

Article link copied.

In mid-January, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer unveiled the AI Opportunities Action Plan, an ambitious roadmap designed to solidify the UK’s position as a global leader in artificial intelligence (AI).

The initiative covers a wide spectrum of AI applications, from practical tasks such as detecting potholes to the ambitious long-term goal of transforming the UK into an AI “superpower”, positioning it as “a future revolution on the horizon”.

Below we explore the key elements of the new plan.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

What is the UK’s AI Opportunities Action Plan?

It is an initiative to increase the UK’s use of AI, as part of the government’s overall plan to help turbocharge growth and boost living standards in the UK.

The prime minister emphasised that the aim is for the public sector to spend less time doing admin and more time delivering the services that communities rely on. He explained that “we don’t need to walk down a US or an EU path on AI regulation – we can go our own way, taking a distinctively British approach.”

Starmer continued by highlighting practical applications of AI, such as assisting small businesses with record-keeping and efficiently identifying infrastructure issues. The prime minister described these investments as essential for securing “the jobs of tomorrow”.

The plan has garnered support from leading technology firms, with commitments totalling £14bn and the creation of 13,250 jobs – a massive boost to the macroeconomy. This investment underscores the private sector’s confidence in the government’s vision for AI integration.

UK technology secretary Peter Kyle also promised that the government’s AI initiatives aim to “open up new opportunities rather than just threaten traditional patterns of work”.

Where will growth be focused?

The plan includes the creation of AI Growth Zones, specific geographical regions where development efforts will be concentrated.

The point of these zones is to foster public-private partnerships, enhance digital and energy infrastructure, and support sustainability initiatives. This, in turn, will drive local economic growth and job creation.

The first zone will be established at Culham, Oxfordshire, home to the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). The government and UKAEA will seek a private-sector partner to develop one of the UK’s largest AI data centres, with the selection process set to begin in spring 2025.

The government saidthese areas will also serve as a testing ground to explore how future sustainable energy systems, such as fusion, might be able to power artificial intelligence.

What concerns do people have?

Generative AI (commonly known as GenAI) consumes large amounts of energy – for example, creating an AI image uses the same amount of power as charging a phone.

Starmer’s government has relaxed UK planning laws to open the doors for more data centre construction projects. This has been a source of much opposition, due to the high energy needs.

To address the issues raised by pressure groups surrounding energy demand, the UK is setting up a new AI Energy Council, chaired by the science and energy secretaries. It will work with energy companies to better understand the energy demands and challenges of AI.

Discussions are taking place to see if miniature nuclear reactors can help solve the problem.

Why build a new supercomputer?

The UK government will also build a new supercomputer, joining two existing ones at the University of Bristol, after scrapping previous plans for one at Edinburgh University. This machine will match or exceed the speed of Isambard-AI, the UK’s fastest supercomputer.

Part of a broader investment in government-owned AI computing, the initiative follows recommendations from Matt Clifford, AI adviser to the prime minister. Nearly all of his 50 proposals have been accepted, including plans to build the equivalent of 100,000 GPUs – graphics processing units, which are essential for AI – by 2030.

State ownership aims to ensure data sovereignty (giving the collecting country governance over the data) and allow rapid allocation of computing power for key national priorities. This funding is separate from private AI infrastructure investments, with the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) set to release a long-term computing strategy in spring.

Peter Kyle speaks to University College London East students.

Picture by: Alecsandra Dragoi | DSIT | Flickr

How could AI improve education in the UK?

The UK government is actively investing in AI to enhance education by supporting both teachers and students. A £3m pilot, funded by DSIT, aims to improve AI content and data accessibility, while additional funding supports AI tools designed to ease the burden of marking and feedback. The government is joined by independent public bodies, such as the Oak National Academy, which has launched Aila, an AI-powered lesson assistant designed to streamline lesson planning and reduce teacher workloads.

To ensure responsible AI adoption, the government is developing training resources and an online toolkit for educators. An evidence board will assess AI’s impact on teaching and learning, providing suitable guidance for schools. Ofsted (the government’s education regulator) is also conducting research into how early-adopter schools are implementing AI, focusing on governance, educational outcomes and potential risks.

Beyond schools, efforts are underway to expand AI education pathways and increase the number of AI graduates with industry-relevant skills.

With AI already saving teachers valuable time – potentially three and a half hours per week – the government sees it as a key tool in shaping the future of education.

Are there any risks?

While the UK’s AI strategy is ambitious, challenges remain. Critics argue that focusing on advanced AI systems may overlook broader risks, such as the use of copyrighted material in AI development. Ensuring effective premarket testing without stifling innovation, and maintaining a balance between oversight and growth, will be key.

The strategy’s success will ultimately depend on its ability to strengthen the UK’s global AI position. This approach marks a bold departure from the EU’s regulatory model, setting the UK on a distinct path in AI governance.

This path was evident at the recent Paris AI Action Summit, when the UK refused to signa joint declaration, unlike other countries on a similar trajectory. The statement, which 60 countries signed, set out missions to improve AI accessibility and ensure it is “safe”, “transparent”, “secure and trustworthy”.

A government spokesperson said they didn’t feel the declaration provided “enough practical clarity on global governance, nor sufficiently address harder questions around national security and the challenge AI poses to it”. The US also refused to sign.

What are the next steps?

The UK government says it will continue refining its AI strategy as part of the broader spring 2025 spending review. To ensure the plan’s successful implementation, technology secretary Peter Kyle has established an AI Opportunities Unit within DSIT to track progress of AI initiatives and report regularly.

With key decisions and funding allocations set to take place between this spring and 2027, the next few years will be crucial in determining whether the UK can truly become a global AI leader. Only time will tell if it succeeds.

Written by:

Editor-in-Chief 2024

London, United Kingdom

Born in 2007 in Hong Kong, Jefferson studies in Reading, England and plans to attend a university in the United Kingdom.

Jefferson joined Harbingers’ Magazine in 2023 — first as a contributor, but quickly became the UK Correspondent. In 2024, he took over as the editor-in-chief and acting editor of the Politics section.

Additionally, Jefferson coordinates the Harbingerettes project in Nepal, where a group of 10 students has journalism-themed lessons in English. He spends some of his holiday reporting on the development of LGBT+ rights in Asia (one of his articles was published by The Diplomat).

He is interested in philosophy, journalism, sports, religious studies, and ethics. In his free time, Jefferson – who describes himself as “young, small and smart” – watches movies, enjoys gardening and plays sports. He speaks English, Mandarin and Cantonese.

Edited by:

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism