16-year-old Sophie interviews experts and voters on how the far-right attracted young votes

An anti-refugee message during a far-right rally in Warsaw, 6 September 2025.

Picture by: ZUMA Press, Inc. | Alamy

Article link copied.

September 26, 2025

Political identities: How young voters tipped the scales in Poland’s presidential election

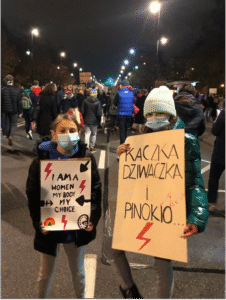

At the ripe old age of 11, I went on my first political protest. Squeezing my mom’s hand, I clutched my Covid mask as we joined the crowd gathering in the centre of Warsaw. Under my arm, I tucked a poster I had meticulously crafted earlier, and now raised for everyone to see. It read: ‘I AM A WOMEN. MY BODY, MY CHOICE.’ (My English has much improved since.)

It was October 2020, when the Polish Constitutional Tribunal (TK) banned nearly all legal abortions in Poland. The Polish president, Andrzej Duda, welcomed the ruling. My mom found out about the protest and she was determined to go, and so was I – determined, nervous, excited and proud that I am standing up for my rights as a woman.

However, at the time I didn’t understand why our government was making decisions about our bodies, that is why I wanted change. Later, I also learned that on that day, 100,000 people took to the streets.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

As we got to the front of the protest, I saw a group of men and women dressed in black. I was confused – were they a part of the protest? My mom explained that they were not; they supported the TK’s decision to limit access to abortion in Poland.

Fast forward five years, I am now 16, and Karol Nawrocki, a candidate of the conservative Law and Justice party (PiS), was elected as Poland’s next president. Nawrocki is expected largely to follow Andrzej Duda’s agenda, including support for restricting legal access to abortion.

When reading about the election, I was struck by one statistic: according to Ipsos, more than 53% of the youngest voters (aged 18–39) cast their ballot in favour of Nawrocki. I realised that it was young people who helped Nawrocki into the Belweder. This brought back the people in black I saw at the protest.

I got curious. Who were they? What shaped their political beliefs? What drove young voters towards conservative and nationalist candidates?

I had a chance to get a better understanding when I attended the Columbia Pre-College Journalism Program this summer, during which I spoke to several voters from both sides of the political divide, as well as experts, including a political science professor and the director of the Polish Atlantic Council.

Many young voters like Nawrocki’s stance on immigration. According to Eurostat, the European Union’s statistics office, Poland has experienced significant levels of immigration from outside the EU in recent years, in some years the highest in the EU. According to data released by Poland’s Social Insurance Office (ZUS), by the end of 2023 there were more than 1.1 million immigrants in the country, and immigrants made up 7% of people registered in ZUS’s systems.

Nawrocki promised voters to “be guided by a simple but important principle: Poland first, Poles first.” He said that Poles should not have to wait for medical appointments, while the native population should get priority placement in schools. “Polish children must have priority,” he stated.

11-year-old Sophie (L) at a Warsaw protest against the ban on abortion in Poland, 30 October 2020.

Picture courtesy of: Sophie Rytel

This resonated with some young voters, who believe that immigrants compete for jobs and put a strain on public services that are meant for Poles. Patricia, a 26-year-old financial auditor, voted for Nawrocki because of his stance on migration. She believed his policies will help Poland reject the obligations regarding migrants under EU regulations – as Forbes explained, the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum “in theory could oblige Poland to take more refugees from the Middle East and Africa or face penalties.”

In light of that, Patricia did not mind that Nawrocki never held any significant elected office before becoming the president. “He’s not a politician, so he brings a different perspective,” she said.

“Under Nawrocki’s rule, it will be much safer,” said another voter who supported the right-wing candidate.

Rafał Trzaskowski, Civic Coalition’s (KO) liberal candidate, who in the second round was endorsed by a wide coalition from centre-right to centre-left, campaigned with a pro-European, liberal manifesto.

Amelia, a 22-year-old Brown University graduate, voted for Trzaskowski. “He campaigned on keeping Poland open, democratic and aligned with European values,” she said, underlining that as mayor of Warsaw for six years, Trzaskowski supported equal rights for women, minorities and the LGBTQ+ community.

Marta, a 29-year-old analyst at one of the big-four consulting companies, said that Trzaskowski secured her vote as someone who “would represent our country in a much more professional manner”. “He is a person who carries a lot of class and a kind of professionalism in both political statements and everyday speech,” she said.

However, what appealed to Amelia and Marta did not resonate with the majority of young people, who sided with Nawrocki’s campaign, which mixed nationalist elements with emphasis on traditional and Catholic values, and their expression in public.

Alex Szczerbiak, professor of politics at the University of Sussex, explained: “[Some voters would] see the woke left as a much bigger threat to their personal freedom than the religious right, [believing] the woke left will try to cancel them in social media, which is really important to them.”

He underlined that social media is crucial to Gen Z voters, for whom the fear of being silenced online for expressing controversial views is what drives them towards right-wing parties. In Poland, both PiS and the nationalist-right Confederation party promise to defend freedom of speech and religious expression against the ‘woke left’.

Nawrocki’s past as a boxer and fights promoter adds to the image of a strongman, unafraid to be politically incorrect. Aaron Korewa, director of the Atlantic Council in Poland, an organisation that examines political, economic and security issues, assessed that Nawrocki “looks like he’s protecting traditional values and Polish pride” and promised change, with clearly outlined policies to address certain problems, while Trzaskowski’s promises appeared “watered down” – more complex, liberal, general and lacking a clear goal.

Korewa added that Nawrocki’s anti-immigration stance indirectly attracts tradition-oriented voters, who also want to preserve the traditional division of male and female roles in society, but in the case of Gen Z, a significant driver was disillusionment with the current government of Donald Tusk.

Korewa indicated that Tusk, having won the parliamentary elections in 2023, under a manifestothat later drowned in his coalition’s political disagreements, is not able to prevent KO’s voters from looking for alternatives on the political right.

Additionally, although Nawrocki’s campaign was indirectly supported by PiS, he presented himself almost as an independent, which resulted in his ability to secure votes from the radical and extreme far-right, whose base recruits from disillusioned PiS voters. By contrast, Trzaskowski was very closely tied to the liberal Civic Platform – unmistakably liberal and progressive, he was only able to reach those voters.

Marta, who voted for Trzaskowski, says she made her choice at the polling station, but democracy involves divisions. “Whether I’m in a room today with someone who voted for Trzaskowski or with someone who voted for Nawrocki, I feel that we’ll always find common ground and shared values – we just have to be open to it.”

Five years ago, the younger version of me, the 11-year-old girl at the protest, was confused to see the counter-protestors. By 16, I learned that political beliefs are complex, and voters cannot be only explained by their age. But sometimes I think about the young girl at that protest, concerned for the rights of women and minorities in Poland, and the conservative drift of my country.

While I now better understand those Poles who want to preserve Polish traditions, and who hope for progress, in my mind I still look at these people in black I saw five years ago and hope that we’ll be able to find a middle ground, not just push the other side out.

Written by:

Contributor

New Jersey, US

Born in 2009 in Moscow, Russia, Sophie Rytel studies in New Jersey, United States. She is interested in journalism and plans to study humanities-related subjects in the future, but isn’t sure yet.

Sophie plays volleyball, swims and rows on a lake; she also enjoys writing and drawing. In her free time, she watches Fast&Furious movies.

Sophie speaks Polish and English.

Edited by:

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism