16-year-old Lola travelled to Bali to explore the island’s unique approach to psychology and mental health

Lola with Balinese student Ni Kadek Artanti Laksita.

Picture courtesy of: Lola Kadas

Article link copied.

September 26, 2025

Bali’s complicated relationship with mental health: A look from inside

On the Indonesian island of Bali, mental health is rarely confined to psychology and medicine. Healing here is rooted in spirituality, rituals and community. Where much of the Western world frames mental health as a clinical matter, in Bali it is a matter of mind, body and soul.

This is especially striking given Bali’s position within Indonesia. More than 87% of the nation’s population is Muslim, but the island remains a Hindu hub, practicing its own distinct form of Balinese Hinduism, which blends Hindu teachings with animism (the belief that objects, places and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence) and ancestor worship.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

Combined with its famous landscapes and temples, this gives Bali an image of tranquility and paradise. Yet, beneath this image lies a more complicated reality, particularly when it comes to mental health services for local people.

Before arriving in Bali in July 2025, I knew little beyond what my research suggested – that Western-style mental healthcare is not widespread, and people are far more likely to seek out a traditional healer than a psychologist. Religion and spirituality play central roles, often shaping how people interpret mental illness, sometimes with stigma and misunderstanding attached.

These findings were both confirmed and challenged during my interviews with professionals and community members. I discovered a more complex picture of mental healthcare on the island.

Pasung and the politics of silence

One of the most alarming issues I encountered was pasung – the practice of physically restraining and confining people with mental illness within their communities or in institutions. Although pasung was banned by the government in 1977, it continues: in 2016, almost 19,000 people were still living under such conditions. These can be dire: people are sometimes chained or shackled, neglected, not fed or washed properly and ignored.

The subject remains taboo. “If we uncover this, it means that Bali won’t look good anymore, and the island will no longer be seen as a paradise,” said Dr Cokorda Bagus Jaya Lesmana, secretary of the Suryani Institute for Mental Health. In 2014, the institute staged a photo exhibition to expose the reality of pasung, resulting in objections from a local governor who feared it would harm Bali’s image.

Tourism remains vital to Bali’s economy, with 16.4 million people visiting in 2024. This tension between protecting tourism and addressing suffering continues to shape public conversations.

Dr Lesmana recalled government efforts to eradicate pasung, most notably through a national programme launched in 2010, which estimated that 44,000 people with mental illness were affected. But progress soon stalled. “After five years, nothing happened,” he said. “They don’t know where the patients are, there’s no data by name or by address, only projected data.”

Two approaches to psychiatry

In Bali, only a handful of organisations work on mental health. I visited two of them: the privately run Suryani Institute, and the government-run Komunitas Peduli Kesehatan (better known as Kopi Kental), which has no online presence.

The Suryani Institute blends meditation, talk therapy and medication, seeking to bridge traditional practices with Western psychiatry. “In the West, privacy is important, but here community is important,” said Dr Lesmana. “If we just use the Western concept, we become alien to our people.”

This privately run institution, where patients pay for treatment, was clean and extremely well organised, reflecting its emphasis on innovation and integration.

In contrast, Kopi Kental has emerged from a completely different background. Once a homeless shelter, it was converted into a psychiatric centre in 2017. The live-in patients receive meals three times a day, medicine (the cost of which is covered by government insurance) and basic accommodation that struck me as rough and inadequate.

I Meda, the head of the facility, explained that resources are stretched thin, with no paid staff and only ten volunteers to take care of 29 patients. “The biggest challenges are funding, finding volunteers and taking care of the patients,” he said.

The contrast between Suryani and Kopi Kental highlights the uneven landscape of mental health services on the island, one rooted in innovation, the other in survival.

Spiritual healers

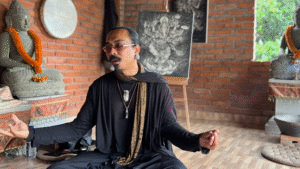

Spiritual healers are also a vital part of Bali’s mental health landscape. Deeply embedded in Balinese Hinduism, they use practices such as hypnosis, chakra cleansing and laughter yoga.

Kadek Saturna, a chakra healer, claimed that he could heal anyone in only 30 minutes: “That is enough. Most people only come one time, just one session, and they already feel healed.” He explained that the main aim is to help activate the heart chakra, because the heart is the centre of all the chakras. “When the heart is open, the energy flows,” he said.

While such promises might sound implausible, their popularity reveals the cultural pull of spirituality. For many Balinese, healers are more trusted, accessible and affordable than psychiatrists.

Some families see them as the first and sometimes only resort for mental health struggles. According to Dr Lesmana from the Suryani Institute, around 70% of Balinese will first turn to a traditional healer when facing personal difficulties.

I also met practitioners of laughter yoga and water purification rituals, each offering different paths to wellbeing but all rooted in the same worldview. What united almost everyone I spoke to was a strong emphasis on prayer and spirituality. These values are not confined to healers alone – they fill everyday life in Bali, where kindness, generosity and a sense of the sacred shape how people approach both suffering and healing.

Gen Z perspective

Younger Balinese, however, are starting to see things differently. I spoke with Ni Kadek Artanti Laksita, a 22-year-old psychology student at Bali International University. Her perspective reflected both curiosity and hope: a desire to study modern psychology while remaining rooted in Balinese tradition.

She agreed that stigma plays a huge role in the reluctance of people to see a therapist. “Especially because when you say you have a mental problem, people will tell you to pray – not to seek help from a professional,” she explained.

She also reflected on the cultural contrast: “As humans, we are very often ungrateful, but Bali always teaches us to be grateful.”

For her, the key lies in balance. “In Bali, there are many places where you can do yoga, which helps you to relax and be mindful. I think we have to combine these things. I agree that praying can make people feel better, but it’s not the only way. You also have to seek professional help,” she concluded.

The mental health landscape in Bali is far from simple. Here, religion, tradition and culture remain inseparable from psychology. This can mean stigma and silence, but it also opens space for a community-based support system that is rarely seen in the West.

Institutions like Suryani prove that it is possible to integrate Western psychiatry with Balinese values, creating treatments that are both modern and culturally resonant. Whether through yoga, prayer or professional help, Bali’s evolving approach offers a good reminder that mental health is never only clinical but also deeply human.

Written by:

Society Section Editor 2025

Budapest, Hungary

Born in 2009 in Budapest, Hungary, Lola has lived in Budapest and California, US. She is interested in music, pop culture, politics, and mental health, and plans to study psychology.

Lola joined Harbingers’ Magazine in the summer of 2024 as a contributor during the Oxford Pop-up Newsroom. After completing the newsroom and the Essential Journalism Course, she became a writer in the autumn of the same year, covering society and public affairs. Her strong writing skills and dedication to the magazine led to her promotion to Society Section Editor in 2025.

In her free time, Lola plays guitar, piano, and volleyball, enjoys going to concerts, and creates various types of studio art. She is also a fan of Taylor Swift’s music.

Lola speaks English, Hungarian, French, and Spanish.

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism